Auke Visser's International Esso Tankers site | home

The Esso Fleet Lay-up site in the 1930s - Part-1

Tankers in the Patuxent: The ESSO Fleet Lay-Up Site in the 1930s

By : MERLE T. COLE

THROUGHOUT the 1930's. a significant portion of the world‘s largest tanker fleet lay idle in the Patuxent River near Solomon's. Maryland. As the company history summarizes, “the tankers had difficulty in adjusting to the ups and downs of the oil industry in

the late 1920's and the let's.”'

1. THE ESSO FLEET

In the earliest major case of “divestiture," the United States Supreme Court handed down its famous 1911 decision ordering the mammoth Standard Oil Company to dissolve. Among the many separate, but similarly named, companies emerging from the dissolution was the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (incorporated in Delaware). This entity was most commonly

referred to by shorter names such as “Jersey Standard,” the “Delaware Company." and; after 1923 - “ESSO” The latter was formed from the initial letters of“Standard Oil."‘

Jersey Standard started its new life facing an acute shortage of tanker tonnage. and relied mainly on chartered vessels and those of the Deutsch-Amerikanische Petroleum-Gesellschaft (DAPG), a German affiliate, to transport the company’s crude and refined petroleum products. Not until 1913 were the company’s first tanker hulls laid down. These ships, the William Rockefeller and John D. Archbold, joined the fleet the next year. With the outbreak of World War l the company’s Foreign Shipping Department. which managed all marine operations, gained control of DAPG vessels interned in neutral American ports and “almost overnight the company fleet expanded from two to twentyeight tankers.” Additional tonnage was constructed to meet subsequent wartime needs, so that by 1917 Jersey Standard owned forty-one tankers, “more than a quarter of all American-register tankers afloat at the

time.“

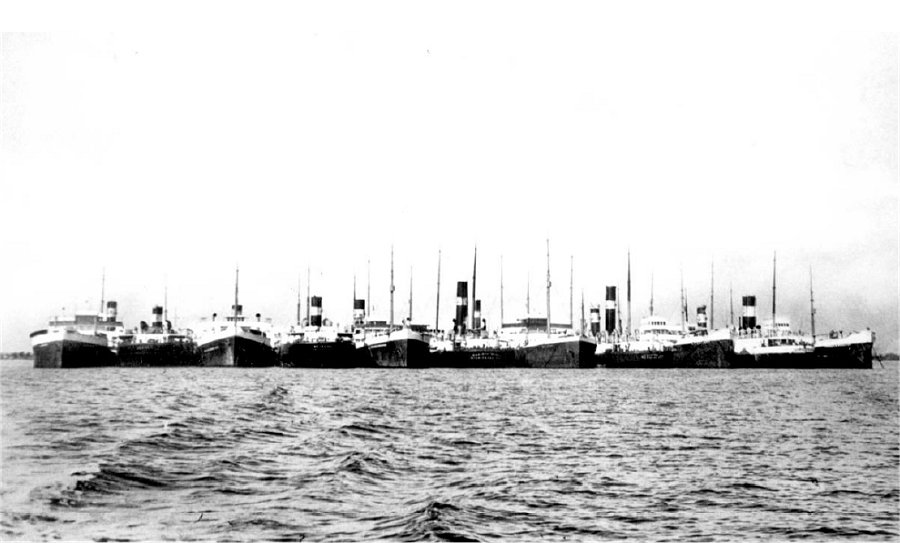

Mothballed ESSO Tanker fleet, Patuxent River, Maryland. Group No. 1, 1930-1931, left to right: L. J . Drake, Beaconhill, Beaconstar, Beaconoil, Benjamin Brewster, Christy Payne, W. H. Libby, Livingston Roe, M. F Elliott, W. H. Tilfard, and Thomas H. Wheeler.

(Courtesy of the Calvert Marine Museum, Solomons, Maryland.)

The Jersey fleet - defined as “the tankers of affiliates in which the parent company owned the majority of the stock” - was in excellent condition after the war, notwithstanding the loss of both of its two original tankers to enemy action.

Half the 44 vessels Sailing under the Jersey flag [in 1919] were less than three years old; 27 other tankers were owned by

affiliates. This combined fleet of 71 ships was the second largest privately owned tanker fleet afloat. being surpassed only by the Royal Dutch-Shell armada of 100 vessels.‘

The huge size of the Delaware Company’s fleet is evident in the following comparison with other fleets in the petroleum industry:

Immediately after the war, the world witnessed an international shipping boom of unprecedented intensity. Many companies, including Jersey Standard, placed orders for thousands of deadweight tons of new vessels. (Deadweight tonnage is the difference between a vessel’s loaded and light displacement tonnage, i.e., the ship’s capacity, in long tons.) Then in 1920 the bottom fell out, ushering in a shipping depression which prompted the company to consider selling some of its older fleet units.’

In April 1920, Jersey Standard appointed a shipping committee to study ways to improve administration of its marine operations. David T. Warner, head of the Foreign Shipping Department. served as committee chair until replaced in both capacities by Robert L. Hague in July. Hague had been marine superintendent for Standard Oil of California until 1918, and thereafter chief of the United States Shipping Board’s construction and repair division. Under Hague’s management, the newly renamed Marine Department undertook a series of economy and efficiency measures to reduce fleet operating costs.‘

It was an uphill battle as the shipping depression ground on into 1921. Fleet management problems were exacerbated by delivery of ten new tankers, contracted for in the boom period immediately after the war. Jersey Standard had no alternative but to lay up part of its fleet, and twelve tankers were idle by the fall of 1921, at a cost of $1,090,000. This dreary situation carried over into the next year, but losses from the twelve laid-up ships were reduced to $126,600 “by utilizing the vessels for floating storage of oil.” IN 1923 the situation dramatically reversed, and the idle tankers were “emptied of their stored cargoes and dispatched to California

to participate in the oil rush there.”

On 1 October 1927, the Jersey fleet comprised ninety-two tankers - oceangoing, coastal, and inland deepwater. “By far the largest fleet of a single affiliate. in both numbers of ships and tonnage. was that of Standard Shipping, consisting of thirty-eight tankers, of

481.000 tons. flying the flag of the United States.“ Next came the thirteen tankers (161,000 tons) of the Baltisch-Amerikanische Petroleum-Import-Gesellschaft, Mbh (“Bapico"), based in the Free City of Danzig; Imperial, fifteen tankers of 113,000 tons, under British registry; twenty-two other vessels (195,000 tons) owned by eight European Continent affiliates; and four small tankers (10,000 tons), under Peruvian, Argentine, and Dutch registry. Despite the vast scale of this fleet, Jersey Standard exercised only broad policy guidance, and “the affiliates were left to manage their own shipping affairs.”"

Standard Shipping . . . principally carried crude oil and products for Jersey affiliates between ports on the Gulf and Atlantic coasts of the United States. Its ships brought crude oil from Humble tanker terminals to Jersey refineries on the Atlantic Coast or products from Baytown and Baton Rouge for Standard Oil Company of New Jersey to sell in its markets."

The official company history records that 1920-1927 were “outstanding years for the Jersey Marine Department". But the seemingly bright future of petroleum transportation was shattered by the onset of the Great Depression.

The demand for tanker tonnage reached a peak in 1929 and stimulated the building of new ships. The business depression

in 1930 and radical changes in tanker movements quickly created a surplus of tonnage."

The situation was again infamed by delivery of new ships, on the order of a million deadweight tons, and by the purchase of Beacon Oil Company, which added six tankers. In 1929 the company was finally driven to impose “better coordination of the affiliates’ tanker utilization and chartering. . . .” By the end of 1930, Jersey Standard had “a tied-up surplus of 1,500,000 deadweight tons" - twenty-two U.S. flag and five foreign tankers. The tankers were laid up “if they could not earn at least enough to cover their variable, or out of pocket costs." The company could have opted to avoid the economic roller coaster by retaining only a small fleet and chartering ships to meet the rest of its transport needs. But management explained to stockholders its belief that “ownership of tanker tonnage adequate to handle the greater part of the movement of its products is in the interest of its manufacturing and distributing business.”“ Accordingly, the company was faced with the prospect of potential long-term tanker lay-up in response to market fluctuations.

One estimate held that about a quarter of the world’s tankers were idle in 1931. But “concentration on efficiency“ netted “an actual saving” in the cost of Jersey marine operations that year. In May 1932, Jersey Standard bought 95.8 percent of the Pan American Foreign Corporation’s capital stock. This purchase added substantially to “subsidiaries’ reserves of crude oil in Venezuela and Mexico,” as well as acquiring “a large refinery at Aruba. . . In the same year “consumption of lubricating oils . . . showed a marked loss,” and the company experienced the first-ever decline of gasoline sales in the United States. Somewhat ironically, the Pan

American properties included twenty-seven oceangoing and twenty-five small tankers (the latter used primarily to haul crude oil from Lake Maracaibo wells to the Aruba refinery), swelling the Marine Department inventory at a time when an average of twenty-five

tankers were tied up. Lesser numbers of ships were also added by purchase of Huasteca Petroleum Company, Anglo-American Oil Company. Ltd., and Lago Shipping Company, Ltd., during 1932."

In 1933, seven new tankers were added to the fleet, but the average number idle was reduced to seventeen.

This improvement came with the increased demand for petroleum products and the commencement of a large movement of fuel oil from California to U.S. North Atlantic ports in the fall of 1933. This longer voyage replaced the short run from the U.S. Gulf to

North Atlantic ports and absorbed a greater quantity of tonnage.“

Demand for petroleum products remained high during 1934, when movement of 167.7 million barrels “set a new high record for the oceangoing fleet.” Shipments of fuel oil from California “continued in large volume. . . Because of these trends, “All our tankers in

suitable condition were kept fully employed, and freight rates remained steady. . . The company could also report stability and improved earnings throughout 1935. coupled with growing concern over an aging tanker fleet. The evident need for an extensive construction program was tempered by the fact that, under existing national maritime policy, the coastwise shipping

primarily engaged in by the Delaware fleet was “restricted to vessels constructed in American yards and flying the U.S. flag.“ American-built and registered vessels entailed considerably greater expense than the foreign-built, foreign flag tankers used by Jersey’s nineteen affiliates. Two major changes occurred in the Jersey fleet during 1935. On 31 May, the Bapico fleet was

transferred from Danzig to Panamanian registry, refleeting growing concern over Nazi intentions. The newly created Panama Transportation Company joined Jersey as an affiliate." On 1 December, Standard Shipping Company and the marine properties of Pan American Foreign Corporation merged with Jersey Standard‘s Marine Department, with Hague as general manager."

At the end of 1936 Jersey Standard‘s fleet aggregated 191 tankers, at over 2 million deadweight tons -14 percent of the world’s total. But increased demand for petroleum products was such “as to absorb all of the world‘s supply of tanker tonnage," and Standard resorted to time chartering to reinforce its already enormous capacity. “By the middle of [1937] all serviceable

tankers were in operation and freight rates reached the highest level since 1930." Increasing world tension was evidenced by the company’s agreement to participate in a "national defense tanker program” sponsored by the United States Maritime Commission. Jersey agreed to construction of twelve tankers incorporating special features to speed conversion into naval auxiliaries. The

Maritime Commission funded the cost of those special features."

The petroleum industry suffered again in 1938 because of decreased production and increased production costs. For the tankers, “substantially lower freight rates came into effect and prevailed throughout 1938. . . .” In that year ESSO added six oceangoing

tankers to its fleet, but agreed to a Maritime Commission request to sell four of the new “national defense" vessels to other operators.”

Tanker rates were at a low level during the early part of 1939 and then increased sharply as a result of the marine strike.

During the summer. the strike having been terminated, rates receded to those prevailing early in the year. The outbreak of war (1 September) stimulated chartering and all serviceable tankers were again placed in operation.“

Tanker shortages and higher freight rates developed in response to slower voyages to Europe resulting from the convoy system, and “heavy movement coastwise of heating oil due to the [unusually] severe winter.” But despite the convoys, “hampering government regulations, and the sinking of tankers,” industry earnings were greatly improved in the first year of war. ESSO took delivery of four new tankers (two from the “national defense” program), while foreign affiliates lost four ships to submarines and mines.”

ESSO had planned to scrap several "older and less efficient ships. some of which were laid up," but decided in the face of the tanker shortage to recondition - the vessels, which were then “transferred to foreign registry and placed in operation." Between October 1939 and February 1940, the Maritime Commission authorized ESSO to transfer fifteen old tankers to the affiliate Panama Transportation Company. This transfer to neutral registry permitted continued delivery of petroleum products to Great Britain and France, particularly after the Proclamation of Neutrality on 1 November 1939 imposed severe restrictions on American-flag operations in Europe.“

The year 1940 started with a tanker shortage in the face of increased demand. But by mid-year, the French, Low Countries, and Norwegian markets were closed by German occupation, and Italy entered the war as a belligerent. ESSO again faced a surplus tonnage situation, and began laying-up ships in June. By September, thirty-four tankers were idled. Domestic demand soon took up the slack from export losses, with the approach of winter and quickening pace of industrial activity. The resultant “exceptionally heavy” demand caused“ all of Jersey’s vessels [to be] restored to active duty." Tanker shortages continued due to the “high rate of sinking and the additional time required for deliveries within the war zone as a result of the convoy system” (estimated as taking “about twice as long")?

|