Auke Visser's Other Esso Related Tankers Site | home

A story about Lago Oil tankers.

One of the most unusual fleets of tankers was the Lago Fleet, operated by Andrew Weir and Co. Ltd- sometimes known as the “Mosquito Fleet”.

Shallow-draft, trunk deck tankers running between Lake Maracaibo and Aruba, they faced unusual and hazardous navigational problems as they

made their way in and out of the lake in all weathers.

This article gives a brief account of the ships and their activities-now only a memory.

Oil from Lake Maracaibo - by CAPT. F. C. ALEXANDER

MANY seafarers and those interested in the sea and the work of the British merchant seaman may never have heard of the Lago Fleet, officered

on deck and in engine room, by men of the Merchant Navy, English, Irish and Scots (mostly Scots below), who must have shipped millions of

tons of oil from Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela. to Aruba, Netherlands West Indies under the most difficult conditions of navigation. They introduced

the Red Ensign to Lake Maracaibo and kept it flying and the ships sailing in peace and in war.

The Lago Fleet came into being in 1924 and lasted until the Aruba-Lake Maracaibo run ended in 1953 with the pensioning-off of the older hands.

Many of them had been there from the beginning until the end, which came about when the channel from Lake Maracaibo to the sea was dredged

and deepened to take ocean-going tankers.

In 1924 the Lago Oil and Transport Co. Ltd. was formed and registered in Canada. Captain Rodger. of Andrew Weir and Co. Ltd., London and two

associates were sent out to the Curacao-Aruba-Lake Maracaibo area to find a suitable deep water harbour for the trans-shipment of oil from Lake

Maracaibo, Venezuela, where it was being found in vast quantities.

San Nicolas, a bay at the eastern end of Aruba, with a narrow break in the reef which connected it with the sea, was their final choice, and the

widening of the channel and the dredging of the harbour began in the latter months of 1925. To get this bay into shape, a great deal of cutting had

to be done at the narrow entrance and much dredging in the bay itself in order to allow access by the ocean-going tankers of those days.

While this work was being carried on Andrew Weir and Co. Ltd. sent out two small tankers, the Francunion and Inverhampton, to be followed by

a third, the Invercorrie.

In 1926 four more tankers of the Invercaibo class, designed and built for this service were sent out by Weirs.

As the deep water harbour at San Nicolas was not yet ready for ocean-going tankers, these seven ships plied from the Lake to Oranjestad at the

western end of the island, where they discharged into a depot ship. This vessel, in turn, loaded other ocean-going tankers, among them Weir's

Invergordon class. At this time and for many years afterwards the seaward entrance to Lake Maracaibo was an unlightened channel marked by

the usual red and black channel buoys.

The Fairway Buoy to the seaward side of the bar was the only lighted one. When a master got his ship to its vicinity in the small hours of the

morning he usually had to manoeuvre around, invariably in a N.E. gale with a heavy sea running and with his ship in ballast, waiting for the first

glimmer of dawn and a sight of the leading marks poles set up on the sandy shore, to guide him over the outer bar.

It was a weird and nerve-wracking experience going over the outer bar at the break of dawn until one got used to it. With a heavy following sea in

the shallow water the breakers stretched for miles, and were as high sometimes as the rollers in a Western Ocean gale. In going over the bar it

was nothing less than full speed, heading for the beach with its heavy surf just a matter of four or five hundred yards away and trying to hold the

ship on the marks. If the master got off the marks he had “had it'.

With a depth of water of only about 12 ft., in a heavy sea the bumps were frequent and pooping not uncommon. On a rough morning it was not

infrequent for most of the crew to be on deck and I can remember one morning when we pooped a big sea to hear wild yells from aft and glimpsed

an avalanche of water coming through the port and starboard alleyways aft in which were submerged, men, dogs, deck chairs, pots and pans and

ship's gear.

A right-angled turn to the east was made just before the ship hit the beach, which brought her into the buoyed channel, where one had to contend

with terrific rolling and abnormal leeway with a weather beach just a ships length away. Then a couple of miles further on one picked up the pilot

at San Carlos and got under the lee of Zapara Island.

After picking up the pilot there was the inner bar to cross but in going over it the weather conditions were easier. The channel across this bar was

marked out by stakes driven into the sand, with the leaves of palm trees lashed to their tops.

The channel was extremely narrow and could carry only one-way traffic, the loaded ships having preference during high water. Light ships coming

in would sometimes go outside the channel.

Coming out with a loaded ship was a nightmare, for the maximum loaded draft then was 9 ft. Never were tide tables studied so carefully or height

of tide problems so studiously worked out to the inch. It was usual to allow for 18 in. of water under the keel; an extra inch in draft represented a

few more barrels of oil out of the lake, and this despite the fact that heavy seas might be encountered going out over the outer bar. The vessels

just bumped their way out with never any apparent bottom damage.

When going out loaded over the inner bar, one little sheer was all that was necessary for the ship to be ashore. One needed good helmsmen and

the Bonaire (one of the Dutch islands in the Curacao group) men and Venezuelans were good quartermasters. The vessels had their picked men

who were sent to the wheel.

If a ship ran ashore, the pilots, splendid chaps all, invariably gave up in disgust and left it to the master to get the ship afloat again as quickly as

possible. If he took a couple of hours to do this he would lose the high tide at the outer bar and be hours late in arriving at San Nicolas, a little

matter Captain Rodger did not appreciate if it happened too often.

A two and a half-hour run inwards from San Carlos brought the ship to Maracaibo where we cleared, dropped the pilot and proceeded up the lake

to our loading port, either La Sauna or Lagunillas. In this connection the masters did all their own ship-handling at both ends and this meant

constant docking and undocking every day, day and night, every day of the week. with no extra pay for Sundays at sea in those days. What those

masters did not know about handling ships was not worth knowing.

it was not until about November 1927 that San Nicolas harbour was officially opened, when two ocean tankers and five of the Lake tankers entered

and started what was to become one of the world's busiest oil ports. From 1925 onwards a steady flow of new lake tankers were being built and

sent out from the United Kingdom, most of them coming from Harland and Wolff's Belfast shipyard.

Storage tanks were going up at San Nicolas and in 1928 it was decided to build a refinery, power house, and houses for the people who would run

it. At the beginning of 1929 the power house had been built and was in operation, together with the first of the oil-refining plant.

With the extension of the refinery, houses going Lip, roads laid out, and a hospital and church built, it was not long before a fair-sized township

developed and covered the land where the cactus plants formerly grew in profusion.

During the years between 1929 and 1939 the haulage of oil from the lake continued. One of the `Inver' type tankers was converted to a suction

dredger and the outer and inner bars were dredged to a depth of about 17 ft., which certainly made things easier for the ships.

Some of the vessels went farther afield to Eastern Venezuelan ports, to Guiria and other ports where oil was being produced and piped to the sea

and it was not unusual to go to some part of Venezuela, lie offshore, pick up a submerged pipeline, load up and proceed to Aruba with a load of

crude. They carried fuel oil to most of the West Indian islands and helped to keep the power houses in Havana and Santiago de Cuba supplied

with fuel.

Frequent runs were also made to the Panama Canal Zone where the larger ships were docked and also frequent runs to east coast United States

ports.

That 10-year period also had its slack times when half the fleet was laid-up for months, when the world demand for oil was low. Then would come

a rush period when the ships were running all out to cope with the demand.

When the Second World War began Aruba had its period of the “phoney war.” At the beginning German and Italian ships lay at anchor off Aruba,

but when Hitler started on Holland it was a different matter. The German ships were captured by the British, and a French auxiliary cruiser chased

Italian tankers to the outer bar where they were run ashore.

It was an experience for some of us going over the outer bar to have shells from the Frenchman flying overhead and to watch the Italian crews

walking along the beach making for the Fort at San Carlos.

The war came to Aruba in earnest in the small hours of February 1942. Two of the fleet were torpedoed when lying off the reef and went up in

flames, the refinery was shelled and two or three hours after the first attack three more ships were torpedoed near the outer bar, two of them

Lago ships.

From then until the end of the war the Lago Fleet got its share of attention from the U-boats but apart from a stoppage of a few days until they

got organised, guns fitted and finally formed into convoys, the flow of oil from the lake was uninterrupted, although there were further numerous

attacks.

The products of the crude oil brought out of Lake Maracaibo and refined in Aruba must have gone to all the battle fronts of the world. Tankers

and all types of U.S. naval craft going to the Pacific war via the Panama Canal were loaded or refuelled at San Nicolas.

To replace war losses, new tankers were built in the United States and sent down to help maintain the flow of oil from the lake. After the war

there was a gradual dispersement of the chartered ships and again came slack periods in the world's demand for oil.

About 1948 the writing on the wall began to appear for the Lago Fleet. Pipelines from the storage centres in the lake were being constructed to

deep water in the Paraguana Peninsula, dredgers were at work on the outer and inner bars and in very little time the dispersal and end of the

Lago Fleet took place.

The men of the Lago Fleet were sad and sorry to see it go.

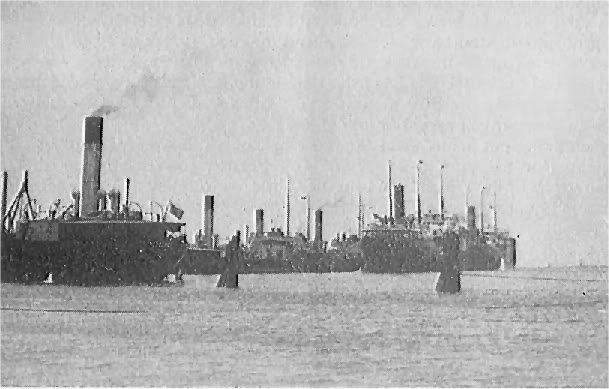

"Lakers" and ocean-going tankers mingle in San Nicolas harbour, Aruba in the 1920's.

THE LAGO FLEET

Name

|

Gross tons

|

Built

|

Builders

|

Amacuro

|

4,352

|

1945

|

Bethlehem SB. Company

|

Ambrosio

|

2,391

|

1926

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Andino

|

3,979

|

1935

|

Howaldtswerke AG., Kiel

|

Avila

|

1,691

|

1938

|

Smith's Dock Co. Ltd., Tees

|

Backaquero

|

4,193

|

1935

|

Furness Shipbuilding Co., Haverton Hill

|

Boscan

|

3,683

|

1937

|

Furness Shipbuilding Co., Haverton Hill

|

Caripito

|

4,352

|

1943

|

Barnes S.B. Company, Duluth

|

Cumarebo ( ex. Creole Fiel-1937)

|

4,058

|

1934

|

Furness Shipbuilding Co., Haverton Hill

|

Esso Costa Rica (ex. Fueloil-42)

|

1,370

|

1919

|

National SB. Co., Violet, La.

|

Francunion

|

737

|

1921

|

Harland and Wolff, Glasgow

|

Guarico

|

4,352

|

1943

|

Barnes S.B. Company, Duluth

|

Guiria

|

4,352

|

1943

|

Barnes S.B. Company, Duluth

|

Hooiberg

|

2,394

|

1928

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Icotea

|

2,395

|

1927

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Inverampton

|

708

|

1920

|

Harland and Wolff, Glasgow

|

Invercaibo

|

2,372

|

1925

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Invercorrie (ex-Palmol)

|

1,126

|

1918

|

Wm. Gray and Co., W. Hartlepool

|

Inverlago

|

2,372

|

1925

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Inverrosa

|

2,372

|

1925

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Inverruba

|

2,372

|

1925

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

La Salina

|

2,395

|

1927

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Lagunilla

|

2,395

|

1927

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Mara

|

4,352

|

1945

|

Bethlehem SB. Company

|

Maracay

|

3,206

|

1931

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Misoa

|

4,193

|

1937

|

Furness Shipbuilding Co., Haverton Hill

|

Oranjestad

|

2,395

|

1927

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Pedernales

|

3,706

|

1938

|

Cantieri Riuniti `dell Adriatico

|

Punta Gorda

|

2,394

|

1928

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Punta Benitez

|

2,394

|

1928

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Quiriquire

|

4,317

|

1938

|

Cantieri Riuniti `dell Adriatico

|

Sabaneta

|

2,395

|

1927

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

San Carlos

|

2,395

|

1927

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

San Joaquin

|

4,352

|

1943

|

Barnes S.B. Company, Duluth

|

San Nicolas

|

2,391

|

1926

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Surinam

|

3,046

|

1929

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Tamare

|

3,046

|

1928

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Tasajera

|

3,683

|

1937

|

Furness Shipbuilding Co., Haverton Hill

|

Temblador

|

4,352

|

1943

|

Barnes S.B. Company, Duluth

|

Tia Juana

|

2,394

|

1928

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Trujillo

|

4,352

|

1945

|

Bethlehem SB. Company

|

Ule

|

3,046

|

1929

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|

Valera

|

4,352

|

1943

|

Barnes S.B. Company, Duluth

|

Yamanota

|

2,394

|

1928

|

Harland and Wolff, Belfast

|