Auke Visser´s Esso UK Tanker's site | home

SHIP SURGERY

Patient: Esso Portsmouth

IT is the fashion nowadays to decry British resourcefulness. Many people seem to find bitter satisfaction in quoting

the ancient cliche: things aren't what they used to be. Well, that is certainly true enough; but perhaps not always in

the accepted, derogatory sense.

Take, for example, the case of Esso Portsmouth . . . Take a damaged ship, slice it in three, remove the wrecked mid-

section and replace it with a new unit. Stated in a single sentence, the operation seems simple enough. There is no

indication of magnitude - and there's the rub.

Take a ship the length of a couple of football pitches, a vessel with a deadweight tonnage of 36,000, whose midship

structure has been ravaged and deformed by fire - take such a ship and slice that in three. Then build a bigger and

better centre section, align it with bows and stern, manoeuvring thousands of tons of steel with absolute precision,

and join up the pieces to make a new vessel.

This is the kind of operation that raises a few eyebrows even onTyneside. But Tyneside has a tradition of accepting

challenges; and they are justifiably pleased with the way they have handled this one. So, incidentally, is Esso. For

the new Esso Portsmouth is now an even better ship than before. As an example of ship surgery, involving one of

the most difficult docking operations ever undertaken on the Tyne, it provides a true success story -emphasized by

the fact that the whole thing began with disaster.

On 8th July, 1960, Esso Portsmouth was badly damaged by fire and explosion. It should have been a happy occasion -

and indeed, up till the time of the disaster, it was - for the ship was the first ocean-going tanker to berth at the marine

terminal of the new refinery on Milford Haven. The previous day, with flags gaily flying, she had arrived from Kuwait

with a cargo of 32,000 tons of crude oil. Everything went well until, early on the Saturday morning, the structural failure

of Number Four unloading arm on the jetty precipitated a series of events leading in quick succession to spillage,

ignition and explosion.

Although, eventually, the bulk of the cargo was saved, the hull structure of the tanker amidships was very heavily buckl-

ed; weather deck fittings and equipment fore and aft were destroyed; and the amidships accommodation and bridge

structure were almost completely gutted. Esso Portsmouth looked a wreck.

When, at last, the flames had been extinguished and the crisis was over, there remained - among many other vital

problems - the problem of the ship's future.

For a time, towards the end of July, she was moored to a buoy off Milford Docks. The experts looked her over, making

rough estimates of the damage and considering the question of reconstruction. Then temporary repairs were carried

out at Milford Haven so that she could be towed back to the Tyne, where she had been built by Vickers-Armstrongs

just a year before.

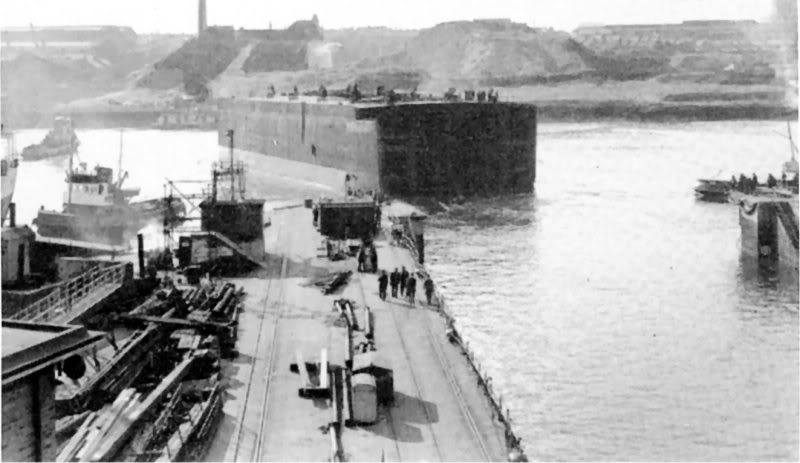

The new midship section approaches the dock to be alligned with .......

It was a depressing homecoming - depressing for anyone who can be moved by the sight and atmosphere of ships.

But not so depressing for the hundreds of shipyard workers to whom Esso Portsmouth was, above all, a promise of

full employment for months to come.

The ship was dry-docked at Wallsend and the full extent of the damage was surveyed. The shell plating had suffered

from stem to poop, and so had the deck plating - especially above Number Three port tank, where it had been blown

out some four feet. The internal damage was equally serious. Between cargo tanks Two and Ten certain bulkheads

had actually been blown down into adjacent tanks. The bridge structure itself was beyond repair; and the heat had

been so intense that aluminium panels on the gangway had melted. Even a derrick had sagged down until it touched

the deck.

It was after the Company and the Underwriters had considered the report of this detailed survey that the major de-

cision was made: the centre section would have to come out. Apart from its scrap value, it was virtually a complete

loss.

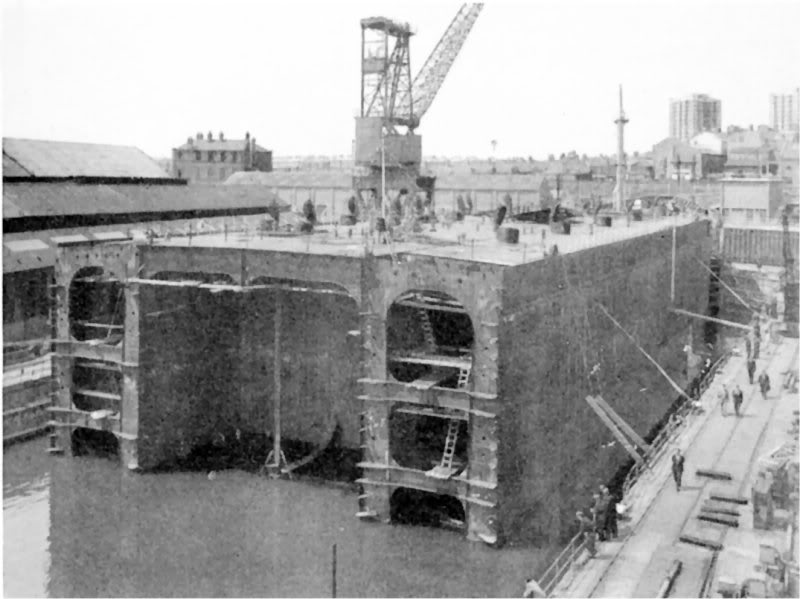

the origial fore section.

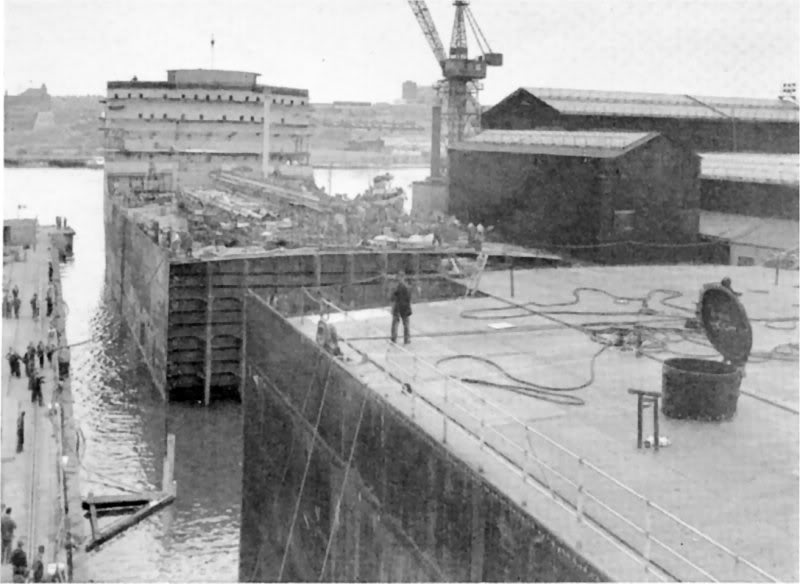

Then the aft section (Below),

with its new superstructure is manoeuvrered into position.

The operation itself would be a long and costly one; the Company was determined to make the most of the oppor-

tunities it presented. There were two choices: the ship could be reconstructed according to her original design, or

she could be modified. The Company had already given much thought to possible modifications. A fairly obvious

one was to increase the size, and therefore the efficiency, of the vessel by installing an extra cargo tank. Less ob-

vious - and certainly less conventional -was the idea of building a new bridge structure on the stern section rather

than amidships.

This latter modification would drastically alter the ship's profile; but there were very strong arguments for adopting

it. Perhaps the most important of these was that it would offer an additional protection to the crew, since no accom-

modation would be directly over any of the cargo tanks. There were also advantages to be gained from it in terms

of general maintenance; and, since the cargo deck would be clear, loading and discharging would become easier

operations.

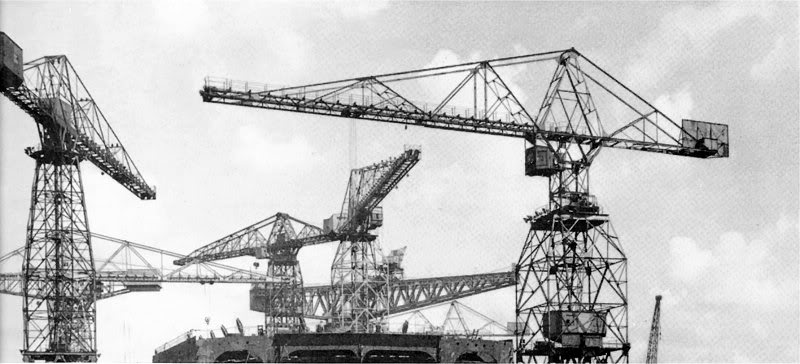

With these major alterations decided upon, the repairs contract was given to the Palmers Hebburn works of Vickers-

Armstrongs, the original builders; and in January, 1961, the new centre section was laid down at their Naval Yard,

Walker-on-Tyne. It took 3,000 tons of steel and four months to build.

Meanwhile, Esso Portsmouth was dry-docked again in March - this time for the operation in ship surgery. Her decks

became alive with the hissing radiance of oxy-acetylene jets, and the constant activity of a swarm ofTyneside

'surgeons'. By the end of the final week in July, Esso Portsmouth was no longer a ship: she was a collection of

pieces. All was ready for the second phase of the operation.

The dock was flooded - and so was the forward section of the ship, which had to stay in position while the stern

and centre sections were towed away. When these had been floated out, the really intricate part of the work could

begin.

The dock was pumped dry once more, and the keel blocks were aligned. These were capped by pieces of soft

wood, three inches thick, which could be compressed. Then, if one part settled high when the stern and the new

centre section were brought into position, ballasting would help to bring about a true alignment of the three hull

sections. Two temporary wooden pillars had already been erected on the starboard side of the keel blocks.

These were to be used as markers in the delicate task of positioning the centre and stern sections, each of

which had a corresponding marker line on the hull.

Again the dock was flooded. Then the new amidships section was towed from Naval Yard, where it had lain

since launching. It was floated into the dock and painstakingly aligned with the forward section, inch by inch,

until its relative position was satisfactory. When this had been achieved, the stern section-now with a newly

styled superstructure - was floated in, and the process was repeated. Although gaps ten feet wide had to be

left between the sections, a true alignment was made. Then the dock was pumped dry.

The next stage consisted of ensuring that the three sections were sitting level with each other on the keel

blocks. Sights were taken along the keel line, and the relative positions of the sections were checked and re-

checked. The results showed that the mid-section was a little higher than the other two. It then had to be bal-

lasted so that the extra weight would compress the soft wood caps on the keel blocks and allow the section

to settle correctly.

Some indication of the difficulties involved may be gained from the knowledge that the entire positioning pro-

cess took about a week.

But, eventually, Esso Portsmouth - the new Esso Portsmouth -was ready to be put together. The joining up

process began. Once more the riveters and welders swarmed about her decks and hull. The longitudinal

framing and stifienings were fitted, then the hull plates began to go on and the gaps between the sections

disappeared.

On 26th September, 1961, Esso Portsmouth, looking like a ship once more, was floated and undocked.

Then she was berthed at Palmers Hebburn quay to complete her fitting out.

By the end of the first week in December, 1961, she was complete and ready for sea. By the end of the se-

cond week, Esso Portsmouth - a ship with a new profile - was on her way to the Persian Gulf for a cargo of

oil, and ever since then has been in continuous service between this country and the Middle East.

Altogether, it took over 4,000 tons of steel and a year of hard work to make a new ship out of an old one and

to fulfil the biggest repair contract ever carried out on Tyneside. The operation was massive and delicate,

skilful and bold.

Repair work of this kind is called ship surgery - an apt description, for it is just that.

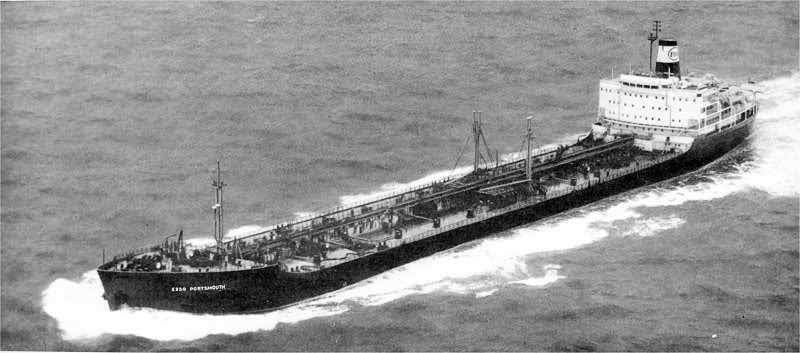

The old "Esso Portsmouth" with bridge amidships.

The new "Esso Portsmouth" with bridge astern.