Auke Visser´s Esso UK Tanker's site | home

Motor Shipbuilding in Europe

Source : Pacific Marine Review, Volume 17, July 1920.

Motor Shipbuilding in Europe

SIGNS are already here known Norwegian shipowner, is to inaugurate a new service between Scandinavia and California, via the Panama Canal, to be operated by motor ships, the first of which (a 9000 ton deadweight capacity vessel) has just been launched by Burmeister & Wain at Copenhagen. It is hoped that all of these vessels will be ready for commission by the end of the year, although with the existing' shipbuilding delays, it is improbable that this anticipation will be realized. When these ships come into service it is stated that reduced freights will be charged and another Norwegian shipowning firm has recently announced its intention of lowering its freights; it is enabled to do this by the purchase from the Norwegian government of three motor ships which during the war have been operated by the Shipping Department of the government. These are three old steamers built on the Clyde which were converted to motor vessels for the East Asiatic Company some time before the outbreak of war, this company then selling them to the Norwegian government.

Scandinavian shipowners are confident that with motorships freights can be cut down nearly 50 per cent below present levels and still enable the owners to run at a profit, while steam ships burning either coal or oil will become unprofitable when this anticipated freight cutting commences. It was definitely stated by the Trans-Atlantic Company of Gothenburg - the owners of steam and motor ships - that the latter could carry freight from America to Sweden at approximately 50 per cent of the cost to the owners of corresponding steam ships. So strong is the belief of the Trans-Atlantic Company in the motorship that, in addition to the orders for eight 9400-ton motorships which they have placed, they have commenced the conversion of their large fleet of steamers to motor power by the installation of a 1700 - horsepower two-cycle Polar Diesel engine in one of their 5000 - ton steamers, the Bolmen.

New Oil Engine Builders As showing the urgency of the motorship position in Europe, no fewer than four of the leading shipbuilding and engineering firms in Great Britain have, during the past month, taken out licenses for the construction of Diesel marine motors. They are forced to this end owing to the fact that shipowners are asking for their new vessels to be equipped with oil engines instead of steam machinery, and as it is impossible for a firm to develop a marine Diesel engine itself without prolonged experimental work, the manufacturers are finding it easier to take out a license from builders who have gained this necessary experience over a long period of operation at sea. Messrs. John Brown & Company, Ltd., the famous Clydebank firm who built the Lusitania and the largest British battle cruiser, the Hood (just completed), have at last come to the conclusion that they must build Diesel engines and have acquired a license for the construction of the Cammellaird Fullagar opposed piston type, of which a description was recently given in these columns.

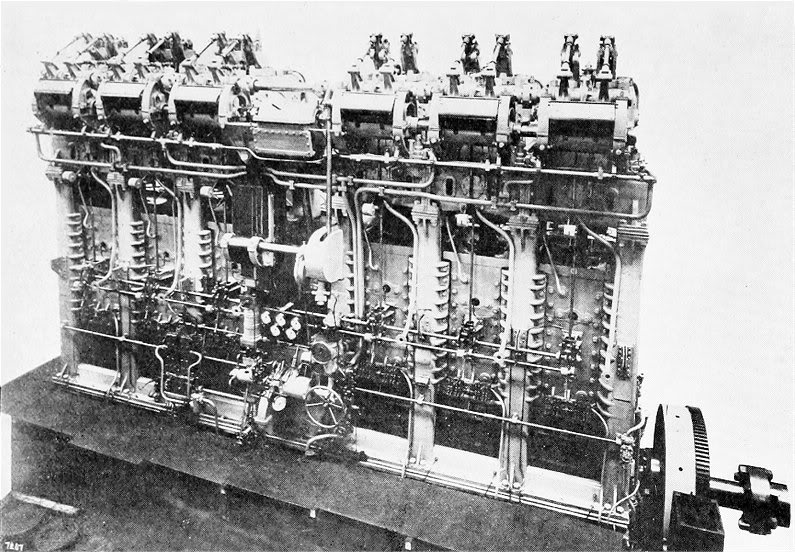

Front view, 1250 h. p. Vickers solid-injection Diesel engine installed in the Narragansett.

It is an open secret that the reason why this type has been adopted is that it is the most suitable for high powers, as Messrs. J. Brown & Company wish to develop the motor passenger liner for the Cunard and other companies with vessels running between Great Britain and America. Already plans are being prepared for 6 - cylinder engines with cylinders 28 inches diameter which will give an output of 5000 horsepower, and preparations are being made for a 6-cylinder 30-inch diameter engine which is to develop 7500 b.h.p. or 15,000 b. h. p. in a twin-screw ship. With such machinery, the Atlantic passenger motor liner is coming within reasonable distance.

Another famous firm which has taken up Diesel engine manufacture within the past few weeks is Messrs. Alexander Stephen & Sons, Ltd., who have acquired a license for the Sulzer two-cycle motor. It is interesting to record that this license was taken up on the advice of the British India Steam Navigation Company, who wished to place an order for a motor vessel with Messrs. Stephens and decided that the Sulzer type would be the most suitable for their purpose. The new ship, which will be the fourth for the B.I.S.N. Co., will carry about 11,000 tons and be fitted with two 1600 b. h. p. engines.

Two other well known Clyde marine engineering firms, who until now have adhered rigidly to steam engine construction, have just adopted oil engine manufacture, and it is a matter of special interest that both have pinned their faith to the Cammellaird Fullagar type, so that there are now three licensees for the manufacture of this motor in Great Britain besides one in America.

Among other orders that have been placed for motorships during the past month are four tank vessels for the newly "formed oil transportation concern, the Scottish Tankers, Ltd., all of which are to be built by Vickers. They will carry 10,000 tons of oil fuel on a speed of 11 knots and be fitted with a couple of 1250 b.h.p. Vickers solid injection Diesel engines. The Bibby Line has ordered a new motor vessel of 7500 tons gross, named the Somersetshire, a sister ship to the Dorsetshire, referred to last month in Pacific Marine Review, which will be built by Harland & Wolff at Belfast and equipped with engines of their manufacture. This ship, together with the Dorsetshire, will trade to the East. In the course of a few months' time, the Glen Line, the British India Steamship Navigation Company, the Bibby Line and the Ellerman Line will all have motor vessels running between Europe and India and China, which is an exceptionally satisfactory route from the point of view of the internal combustion engined vessel owing to the relative cheapness with which oil fuel can be obtained in the Dutch East Indies and adjacent ports.

A 14,000-ton Motorship

The first 14,000-ton motorship will be completed at Glasgow next month by Harland & Wolff for the Glen Line. She will be the largest ship in the world, carrying nearly 1000 more tons than the Afrika, and, moreover, being equipped with higher powered machinery. The Afrika, belonging to the East Asiatic Company, has two 2250 i.h.p. engines, and the new Glen liner, the Glenogle, is having two 3200 horsepower sets installed. She will thus te the fastest as well as the largest motor cargo vessel afloat, as it is anticipated that a speed at sea of nearly 14 knots will be attained. Three vessels similar to the Glenogle in every respect are being constructed at Glasgow, while in Copenhagen some boats of the same size are being built for the East Asiatic Company to trade between Scandinavia and America.

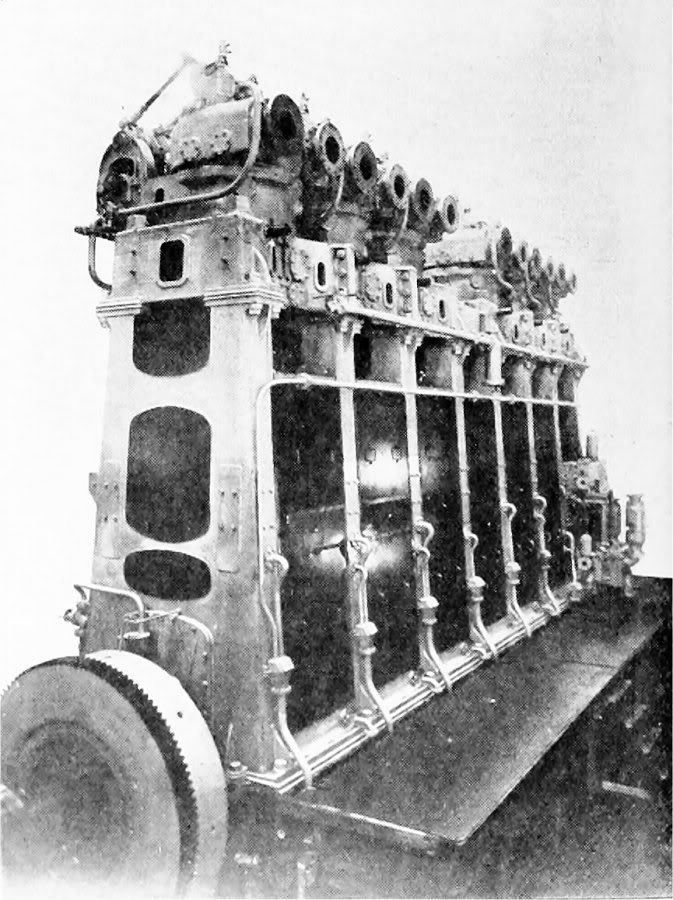

Back view, 1250 h. p. Vickers engine of the Narragansett.

The Motor Tanker Narragansett

The completion of the motor tanker Narragansett by Vickers for the Anglo American Oil Company is of interest to engineers and shipowners, not only in Europe, but also in America, chiefly on account of the novel principles involved in the construction of the machinery of the ship. As is well known, the Vickers firm have invariably adopted solid injection instead of the use of air compressors, and the saving effected is very noticeable in the engine room of the Narragansett, for there are no compressors on the main engine and only a small steam-driven air compressor for the supply of starting air. So far as one can gather from a prolonged trial trip, there are no disadvantages to this system, since the fuel consumption is satisfactory, being 0.44 pounds a b.h.p. hour and the control and operation of the motors appear as satisfactory as those of the blast injection type.

The Narragansett, which is now on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New Orleans, carries about 10,000 tons of cargo at a speed of 11 knots and is fitted with two Vickers engines of 1250 b.h.p., running at 118 r.p.m., but capable of maintaining a speed of 125 r.p.m. continuously, when the power developed is 1350 b.h.p. There are six cylinders, 24 1/2 - inch diameter by 39-inch stroke, and the engines operate on the four-cycle principle.

The general features of the construction of cylinders and framing can be noted in the illustration, from which it will be seen that the cylinders are supported by cast iron columns in a somewhat similar manner to that adopted on Vickers submarine engines. In each cylinder head is an exhaust, inlet and fuel valve, but the starting air is supplied to the cylinders through a non-return valve in the cylinder head, via a distributing box arranged at the control platform. This obviates the necessity of having a mechanically controlled starting valve in the cylinder cover. The camshaft is near the top of the engine, unlike the Burmeister & Wain design, and operates the valves through levers which are pivoted on a maneuvering shaft. This maneuvering shaft is turned when reversing, thus lifting the levers off their cams, after which, without any further movement of the controls, the camshaft is moved fore and aft so as to bring the astern cams underneath the rollers. Following this movement, the maneuvering shaft has a further rotation which causes the valve levers to drop on to the cams. The whole of this movement is carried out by a Servo motor, controlled by a hand lever on the starting platform.

When the camshaft is in the correct position, the starting wheel, seen on the right low down in the illustration, is rotated, which admits starting air to all six cylinders, the fuel valves being cut out of operation. A further movement causes two fuel valves to be brought into service, cutting off the air on the two cylinders; next four cylinders fire on fuel and finally all six on fuel when the starting air is entirely cut off. The whole of this is carried out by rotating the handwheel and the engine runs up to full speed within a few seconds.

The fuel is supplied from a battery of four pumps, seen on the left of the control platform low down on the engine. These all deliver into one main which supplies the four fuel valves at a pressure of about 4000 pounds a square inch. The speed of the engine is controlled by altering the timing and opening of the suction valves of the fuel pumps, which is a method commonly adopted, and in this way the amount of fuel pumped to the fuel valves is varied according to the speed required. A feature of the engine, owing to the absence of the air compressor and the adoption of the four-cycle principle, is that there are very few accessory pumps, these comprising' a small battery of three pumps, one of which is for lubricating- oil, one for bilge pump, while the third is the cylinder water circulating pump, with a small pump above it for the supply of cooling water to the pistons at rather higher pressure than that to the cylinders.

The fuel consumption of the Narragansett is about 11 tons a day, compared with 50 tons a day for a corresponding coal-fired steamer. A second similar ship is now being built for the Anglo American Oil Company, and will be completed in the course of a few months.

|