Auke Visser's International Esso Tankers site | home

BRAVERY AND SKILL - ( Part - 1 )

MS Esso Bolivar

The narratives of submarine attack and salvage in this ship history include acts of heroism and efficiency so outstanding, both in

number and in character, that they truly constitute an epic of devotion to duty and of bravery and skill. In the concluding words of

each of the Presidential citations honoring, without precedent, four officers and men of a single ship, their deeds "will be an en-

during inspiration to seamen of the United States Merchant Marine everywhere."

After the tanker had been abandoned under terrible shellfire, the wounded chief engineer and thirteen other survivors returned to

the battered and burning vessel, with Navy assistance, the next day. Overcoming great difficulties in an amazingly short time,

they brought the floating wreck, still on fire, into port under her own power. Such men as these, in their own memorable way, lived

up to one of the imperishable traditions of the United States Navy - the famous words of Captain James Lawrence - "Don't give

up the ship!"

By what is called the irony of fate, the Panamanian flag tanker Esso Bolivar, built in 1937 by the Fried. Krupp Germaniawerft A.G.

at Kiel Gaarden, Germany, was attacked less than five years later by a German submarine. As if to emphasize this curious twist

of circumstance, the ship w^s manned on her maiden voyage and for two years thereafter by a German crew under the com-

mand of Captain Richard Schlueter, who had been an officer of the German navy in the first World War.

Incidents of Destiny

Aside from this turn of destiny, three incidents occurred on board the Esso Bolivar which, when compared, reflected vast changes

in world affairs. Each of these incidents took place in New York harbor and each one was in sharp contrast -with the others; they

might well have been scenes in a historical drama.

Scene 1 - On the clear summer day of August 3, 1937, the new and handsome motor tanker completed her first voyage, arriving

at New York with a cargo from Aruba. A combination of Company design and foreign construction, she attracted considerable at-

tention, which was due to reports of her fine qualities and modern equipment. As she lay at anchor off Stapleton, Staten Island,

with her white superstructures gleaming in the bright sunlight, news photographers snapped pictures of her and she was board-

ed by Company officials-Messrs. H. J. Esselborn, E. H. LeTourneau, and E. L. Stewart. Accompanying them was a representati-

ve of the United States Maritime Commission, Lieutenant Commander (later Vice Admiral) Howard L. Vickery, U. S. Navy.

A single-screw vessel of 15,255 deadweight tons capacity on international summer draft of 29 feet, 11^4 inches, the Esso Bolivar

has an overall length of 506 feet, 8 inches, and a length between perpendiculars of 485 feet. Her moulded breadth is 69 feet, 9

inches, and her depth moulded is 37 feet. With a cargo carrying capacity of 128,894 barrels, she has an assigned pumping rate

of 4,500 barrels an hour.

Her Diesel engine develops 4,100 brake horsepower and gives her a classification certified speed of 11.6 knots. In addition to

carrying oil in bulk, the vessel has excellent accommodations for twelve passengers.

When Captain Schlueter, a shipmaster of many years' experience, showed his visitors over the ship on her first arrival, he took

them to the wheelhouse, where he said with evident pride and enthusiasm, "She is a marvelously handling ship. She steers

beautifully and one would never suspect she is a vessel of over 15,000 deadweight tons. She is actually alive." It was a good

start for the new ship and a fine day for Captain Schlueter.

Scene II - "Circumstances alter cases." Barely more than two years later a strangely different scene was witnessed aboard

this vessel. The probability that Germany would attack Poland and that Britain and France would then declare war was the

grave situation when, on August 17, 1939, the 41 German officers and crew of the Esso Bolivar, including Captain Schlueter,

were taken off the ship. The Panama Transport Company's responsibility for the foreign crew was met by furnishing them with

living accommodations and subsistence in a New York hotel—until, at their request, all but the radio operator were repatriated,

sailing for Germany on the SS Europa. Captain Schlueter left the United States reluctantly but faced the inevitable, bidding good-

bye to his friends in the Company. He was a good sailor and a fine shipmaster.

Scene HI—The third and best incident occurred on December 10, 1942, while the Esso Bolivar was entering New York harbor.

A tug met her down the bay and messengers boarded her with special instructions for three members of her crew. They were

ordered to Washington immediately, to receive, in the name of the President of the United States, the Maritime Commission's

Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal, awarded solely upon recommendation of the Navy for extraordinary heroism

and meritorious service beyond the call of duty.

Medals and Citations

On December 11, the three medals, with the citations, were presented by Captain Edward Macauley, member of the Maritime

Commission and Deputy War Shipping Administrator, accompanied by Vice Admiral A. P. Fairfield, representing the Navy De-

partment. At the same time, a fourth award made posthumously to the ship's former chief mate was received by his widow,

Mrs. Hawkins Fudske.

The living heroes who modestly received these rare honors from the nation—only three such medals had previously been con-

ferred—were Chief Engineer Thomas J. McTaggart, Fireman-Watertender Arthur A. Lauman, and Able Seaman Charles D.

Richardson. Their citations, with that of Chief Mate Fudske, will be quoted in this chapter as part of the ship's war history.

As stated in The Ships' Bulletin for January-February, 1943: "On December 14, the four medal recipients were the guests of

honor at a luncheon tendered by the Board of Directors of the Standard Oil Company (N. J.), in the Rainbow Room Restaur-

ant atop the RCA Building at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. The Chairman of the Board, Mr. R. W. Gallagher, presided and spoke with

deep feeling of the officers and men who had been lost at sea. He praised the courage and fortitude of those who continue

to carry on, undaunted by the dangers of enemy action.

"Referring to the stirring record of the four Esso officers and men awarded the D. S. M., Mr. Gallagher then presented, on be-

half of the Company, an inscribed jeweled bracelet to Mrs. Fudske and inscribed waterproof wrist watches to each of the

three men. With Mr. Gallagher from the Board of Directors were Messrs. F. W. Abrams, R. T. Haslam, Orville Harden, E.

Holman, T. C. McCobb and F. W. Pierce."

Importance of Aruba-Service Vessels

The importance of the Esso Bolivar in World War II can be made clear by stating that she was one of the tankers assigned to

transporting supplies to the vitally important refinery on the island of Aruba, Netherlands West Indies. She did this in addition

to carrying oil cargoes from Aruba on the return leg of each voyage, thus serving a dual purpose. Other tankers assigned to

this double service during the war - making regular runs from New York to Aruba with fresh water, commissary stores and

refinery equipment - were the C. 0. Stillman (until she was lost), the Esso Aruba, Esso New Orleans (second vessel so nam-

ed), Esso Raleigh (second vessel so named), F. H. Bedford, ]r., J. A. Mowinckel, and Peter Hurll.

Without the supplies continuously furnished by these ships to Aruba and its personnel of more than 6,000 (as well as the

large quantities of crude oil brought to Aruba daily from the Maracaibo oil fields in Lago tankers), the famous refinery could

not have been operated.

The importance of sea power in this regard was suddenly illuminated, as if in a spotlight on the stage of history, when a Nazi

submarine shelled the harbor facilities at San Nicolas, Aruba, and torpedoed two lake tankers on the night of February 16,

1942.

By way of further emphasis, it should be added that the historical importance of the Esso Bolivar and other ships mentioned

above was directly related to the decisive military value of the Aruba refinery to the United States and the United Nations. In

the geography of World War II, rightly called a global war, the Aruba refinery, although covering less than a square mile, was

one of the most important key bases of petroleum supply in the world. With its magnificent strategic location, off the coast of

Venezuela-near its sources of Venezuelan and Colombian oil and only 625 sea miles from the Panama Canal-Aruba is

ideally situated for ocean supply lines in both the Atlantic and the Pacific.

By December, 1943, when its war expansion program was completed, the $81,000,000 refinery processed more than

300,000 barrels of crude oil every day, producing immense quantities of the 100 octane aviation gasoline and special naval

fuels that staggered the enemy on all the battle fronts.

The Esso Bolivar, considering the fact that her fore deep and six of her wing tanks were used only for fresh water, loaded a

considerable amount of oil cargo. For example, on her first wartime voyage, leaving Aruba on August 27, 1939, the vessel

carried 95,625 barrels of topped Colombian crude oil.

In spite of being damaged by enemy action and put out of service for nearly five months, the Esso Bolivar's wartime trans-

portation record, from September 3, 1939 to V-J Day, September 2, 1945, was in summary as follows:

Year

|

Voyages (Cargoes)

|

Barrels

|

1939

|

9

|

839,489

|

1940

|

23

|

2,139,255

|

1941

|

21

|

1,995,713

|

1942

|

7

|

658,125

|

1943

|

12

|

1,103,026

|

1944

|

15

|

1,423,221

|

1945

|

7

|

1,144,853

|

Total

|

94

|

9,303,682

|

The wartime masters of the Esso Bolivar were Captains Ernest C. Kelson, Adolv Larson, Frank E. Wirtanen, Frank I. Shaw,

Thomas B. Christenson, Harry Stremmel, Maurice W. Carter, James M. Stew-art, Abbo H. Kooistra, Robert W. Overbeck,

Martin Olsen, Nils Borgeson, and Andrew W. Ray.

Associated with them were Chief Engineers Thomas J. McTaggart, Cassius 0. Mann, Jr., Fred G. Bush, and Ernst 0.

Beygang.

On February 26, 1942, the Esso Bolivar, commanded by Captain James M. Stewart, with Chief Engineer Thomas J. McTag-

gart in charge of her engineroom, a crew of 44 officers and men, and a Navy gun crew of 6, left New York with a load of fresh

water, commissary stores, and deck cargo. She was armed with a 4-inch stern gun and four 30-caliber machine guns-two

on the wings of the bridge and two on the after deck. All hands were furnished with lifesaving suits. The vessel had a degaus-

sing system for protection against magnetic mines and every precaution had been taken for a complete blackout at night.

Her lifeboats and four life rafts were well equipped and supplied. Two of the lifeboats had outboard motors and radio telegraph

/telephone apparatus.

On the way south. Captain Stewart entered Chesapeake Bay on February 27 for a test and inspection of the degaussing sy-

stem before going to Newport News, Va., for Navy routing instructions. On the afternoon of March 1 the ship got under way

for Aruba.

There were no convoys in that tragic early phase of the war for ships voyaging in southern waters, but the dangerous voyage

down the Atlantic coast was without incident. The men of the Esso Bolivar had seen the wreckage of torpedoed ships on the

Florida reefs and had talked with survivors of enemv action.

The Midnight Watch

At midnight on Saturday, March 7, Second Mate Eldridge J. O'Connell took the 12 to 4 watch, with Harold L. Myers, A.B., at

the wheel. Basil E. Vaught, O.S., reported for standby duty on the bridge and Carl J. Sampson, A.B., went to his lookout sta

tion on the foc'stle head. In the wheelhouse with the second mate was a Navy gunner. The coxswain of the armed guard

(Arnold 0. Cote) was on watch at the stern gun, where two A.B.'s, Charles D. ("Tex") Richardson and Frank V. Phillips, were

standing by to assist four Navy gunners. (Phillips, formerly a clerk in the Personnel Section, Marine Department, enlisted in

the U. S. Army Air Force July 1, 1942. He attained the rank of captain, was credited with three German planes, and received

high military honors.)

Going on watch in the engineroom at midnight were Second Assistant Engineer Neal J. Bowen, Oiler James J. Gallavan,

and Fireman-Watertender Arthur A. Lauman.

About 2:25 a.m., lookout Sampson, who had recently been relieved to get his routine cup of coffee, returned and took the

wheel while helmsman Myers went aft for his turn at brief relaxation in the crew's messroom.

The Esso Bolivar was then at approximately Latitude 19°38' North, Longitude 74°38' West, or about 30 miles southeast of

the U. S. Naval Base at Guan-tanamo, Cuba. The weather was clear and growing warmer; the sea was calm. Bright moon-

light, reflected on the water ahead, silhouetted the tanker as seen from an enemy submarine lurking on the surface in the

darkness astern.

Shelling Begins

At 2.30 a.m., the silence of the sea was broken by the sharp, vicious bang of the unseen submarine's gun and in a few se-

conds the first shell, which narrowly missed the ship, threw up a column of water, ahead. In the wheelhouse, the Navy gun-

ner said, "This is it!" and ran aft to the stern gun. Second Mate O'Connell sounded the general alarm.

Captain Stewart, wakened by the shellfire, put on his lifesaving suit and rushed to the wheelhouse. He first instructed O'

Connell to tell Radio Operator Alvis Jones to send an SOS call and give the ship's position. An acknowledgement was re-

ceived just before a burst of shrapnel put the radio out of commission. Captain Stewart then instructed the second mate

to steer the ship in hard right and left courses. Shells began exploding on deck aft as the submarine found the range.

"The War Has Started"

At 2:30 a.m., Fireman-Watertender Lauman had one boiler steaming and was warming up the other. Second Assistant

Bowen was in the fireroom at that time, mixing boiler compound. As Lauman tells the story, "I said to Mr. Bowen, 'The war

has started. Maybe you will get a bell in the engineroom.' He agreed and calmly went back to the control platform while I

finished the compound. I put more water in the boiler, raised the pressure, and checked all water glasses and valves.

Shells were exploding on deck. In a few minutes Oiler Gallavan came in and shouted, Top, you better get into your lifebelt.'

Then the chief looked into the fireroom and told me the same thing. I said I would put on my lifebelt as soon as I got the se-

cond boiler started."

Chief Engineer McTaggart, roused from a sound sleep by the first shellfire, heard several more explosions as he was put-

ting on his life jacket. For such emergency, he had recently bought with characteristic foresight a rubber ice bag in which-

to put his ship's papers, license, and passport. He shoved the papersinside, screwed on the cap and jammed the water-

tight bag into his pocket as he went on deck.

Climbing to the gun platform, the chief engineer found "Tex" Richardson, who said the firing was off the port quarter and

seemed to come from a considerable distance. The ship's gun had not been fired; the submarine was not visible in the

darkness. McTaggart, thinking it might be possible to outrun the U-boat by increasing the ship's speed, went below to the

engine-room and opened the throttle wide. After a short time. First Assistant Carl L. Sorensen arrived to help his chief.

Third Mate Oscar Owen reported: "I was in my room and came out on deck as soon as I heard the first shell burst. Sever-

al shells then hit the vessel's stern. Fragments and splinters were flying all around us."

Pumpman Conrad S. Eberling, when the attack began, grabbed his life jacket and went through crew quarters to rouse

his shipmates. Finding they were all up, he took his station at the valve of the steam smothering line on the after deck. In

seeking shelter each time he saw, the sub's gun flashes, Eberling never went far from his post -of duty until considerably

later, when Electrician Abraham Stoller came aft with Captain Stewart's order, "All hands go forward."

The third shell that exploded on board the Esso Bolivar started a fire in the galley which soon spread and blazed upward

like a torch, driving the gun crew away from the 4-inch gun.

Meanwhile, Able Seaman Myers, who was in the crew's messroom for coffee when the first shell crashed, roused the

sleeping men aft and then ran to his room, which he shared with Sampson. Hurrying into his lifesaving suit, he grabbed

Sampson's suit and on his way to the wheelhouse left it on the deck near lifeboat No. 2. Myers told Sampson about this

when he relieved him at the wheel, but as Sampson started for the boat deck, a shell exploded near No. 2 boat; the shrap-

nel cut the boat's after fall, leaving the boat hanging over the side, and tore Sampson's life suit to shreds. Sampson then

returned to the wheelhouse and once more took the wheel from Myers.

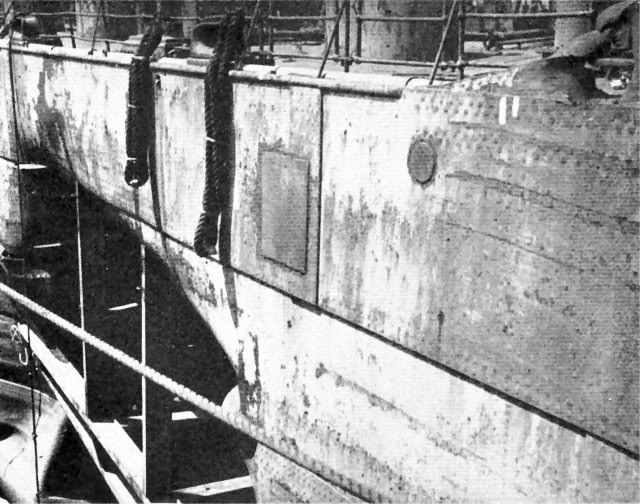

"Esso Bolivar" damage top of wheelhouse.

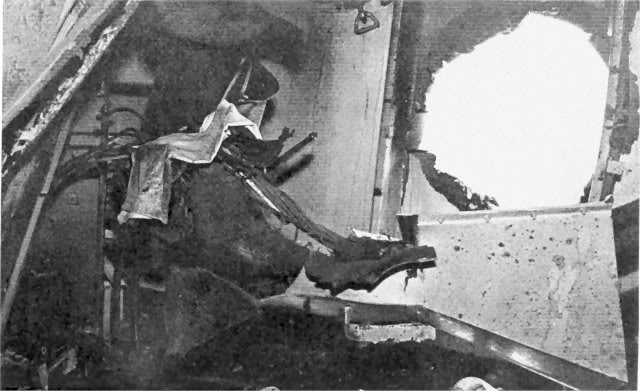

Torpedo hole, Starboard side, looking aft.

Midships house, Port side.

Wreckage in the after deckhouse.

See further : BRAVERY AND SKILL - ( Part - 2 )