Auke Visser's International Esso Tankers site | home

BRAVERY AND SKILL - ( Part - 2 )

See first : BRAVERY AND SKILL - ( Part - 1 )

Galley Set Afire

The incendiary shell that set the galley on fire also cut the feed line leading to the galley range from the tank of fuel oil on

deck. The oil from the tank constantly fed the fire, spreading it until in a few minutes the compartments under the gun

were ablaze. The bulkheads caved in from the intense heat and the flames shot up through the ventilators and hatches,

roaring to a height of 50 feet. The fire would soon cut the gun crew off from the rest of the ship; the blistering heat made

it impossible to man the gun and if the men stayed they would be burned to death. The gun was therefore abandoned.

To quote Chief Engineer McTaggart, "Since I was below most of the time I could not see what was happening on the

gun platform, but heard about it later. When the order came to abandon the ship, two of the gun crew jumped overboard.

The other two were injured by shrapnel, one so badly he was on the verge of unconsciousness. 'Tex' Richardson, him-

self wounded in the hack, urged them to jump, but both refused. The less seriously injured man did not know how to

swim; the other preferred to die where he was. There was no time for argument. 'Tex' dropped them overboard and

jumped in after them."

In the words of Second Mate O'Connell, "The shelling continued and increased in intensity once the submarine got our

range. Shells began hitting all over the vessel and fire started aft. About 3:10 a.m., our steering gear was shot away and

our four lifeboats were either damaged or shot down. As the ship was entirely out of control and circling sharply. Captain

Stewart said 'Ring her off!' and the engine was stopped."

The deck cargo was then burning fiercely. It included cylinders of acetylene shattered by shellfire; the escaping, burning

gas, in addition to the thermite of incendiary shells, set the dunnage on fire and destroyed a number of cargo life rafts

consigned to Aruba. In the light of the red flames reflected on the water, the ship was a splendid target,

"Besides," McTaggart said, "we had over 300 gallons of paint in a storeroom off the engineroom and this caught fire from

the intense heat of the bulkheads. You can't really picture what it was like. Although we were still zigzagging and running

at top speed, the submarine was firing shells as fast as a clock ticks, accurately and with no let-up. Every few minutes

someone was getting hurt or killed."

Chief Pays Tribute to Fireman

Soon afterward, McTaggart heard a deafening crash in the fireroom. Going to the door, he found that a shell had passed

through the casing of the smoke stack, cutting an exhaust pipe. A section of heavy 6-inch copper pipe, about 10 feet

long, had dropped 60 feet down the stack, pulling smaller pipes, glass, asbestos, and wires with it. The whole mess

had fallen almost at Fireman-Watertender Lauman's feet, but he was calmly getting the floor plates clear. Asked by Mc

Taggart if he could remain at his post and keep up steam—as the main engine required the steam auxiliary to keep it in

operation-Lauman replied, "I certainly intend to!" He seemed more concerned about the machinery than the danger. At

that moment,two more shells came through, spraying the fireroom with shrapnel.

"Any other man," McTaggart continued, "would have lost all interest in his work at this point. If a piece of shell had pierc-

ed a boiler, there would have been nothing left of Lauman, but the old man never flickered an eyelash. I started the fire

pumps in case some of the crew might be able to connect the fire hoses. But the shelling was so continuous there

was no opportunity to get the hoses out and soon the ship was burning above and below deck.

"As we kept running, three shells went through the stern and damaged the steering gear. A number of the men were

trying to help the injured; the rest were navigating and attending to their regular duties to keep the ship going. Although

most of the crew had never been under fire before, they were as calm as if the whole attack were nothing but another

drill.

"With the steering gear out of commission the ship went around in a circle, making her an even better target for the sub-

marine. About 3:10 a.m., a signal to stop the engine was received by telegraph from the bridge. We followed instructions

and waited a while. Nothing happened. We tried to "call back by telephone but no contact could be made. I sent the first

assistant to the bridge for instructions.

"Abandon Ship"

"When Sorensen returned to the engineroom through the smoke and shouted that the chief mate had given the order

'Abandon ship!', I told the fireman and the oiler to go to their boat stations immediately; but as chief engineer I decided

to stay a few minutes. If we could leave the engines and boilers in good shape, we could save the tanker if there was

any possibility of coming back. We still had lights in the engineroom and it seemed a shame to run off and let every-

thing go to pieces. Second Engineer Bowen declared himself in on the job; then 'Pop' Lauman said that if we were

staying, so was he! When I ordered him to go on deck, he glared at me. We almost had to knock the old boy down to

force him to leave!

"Bowen and I went to the fireroom, where I speeded up the feed pump so that the boiler would generate steam for a

sufficient length of time to keep the steam-driven cooling water pumps for the main engine in operation, to avoid da

maging the engine and to leave it in as good order as possible for any eventual use." (As stated in The Ships' Bulletin

for July-August, 1943, "For sheer coolness and forethought such conduct under disaster conditions is in a class by

itself.")

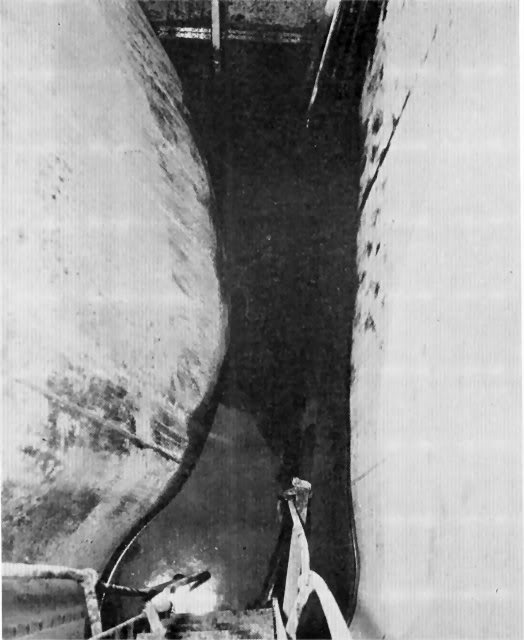

Looking straight down into tank at point of torpedo hit, "Esso Bolivar." No bottom at this point.

Lauman described his difficulty in getting on deck:

"I went above and tried to go through the crew's passageway, port side, but the exit from the engine-room was block-

ed by flames; I tried the starboard passageway, but the fire stopped me again. It was the same with the two officers'

deck passageways. Then I climbed the emergency ladder leading up through the engineroom skylight, but the skylight

cover was only six to eight inches open; it took me several minutes to find that it worked on a pulley. By the time I got

out the ship was on fire and being abandoned; I ran into Machinist Charles H. Low and together we tried to find a life-

boat or raft. No. 3 boat, to which I was assigned, was on fire and No.' 4 was hanging by one davit. With our lifebelts

on. Low and I went down the Jacob's ladder and swam around looking for a raft. Shouting, we heard an answering

call and found 'Tex' Richardson."

Death of the Master

When the engine had been stopped. Captain Stew-art and the other men in the wheelhouse sought protection from

the shellfire by descending to the, starboard side of the boat deck, where a number of men had gathered. As the ship

circled around out of control, shells began hitting the starboard side. One shell hit the wheelhouse; another exploded

on contact with the port side machine gun platform. When the men on the boat deck heard another shell coming over,

they fell flat-all except Captain Stewart, who remained standing near the ladder to the navigating bridge, looking in

the direction of the submarine. As the shell exploded and shrapnel swept the boat deck he was seen to slump over the

ladder rail. Chief Mate Fudske, who had gone to help him, told the men, "The captain is dead."

Thus ended the life of a stout-hearted mariner whose record was excellent throughout many years of service on the

Company's ships-more than twenty-three years as a licensed officer and nearly sixteen years as master.

On taking command, Fudske, as previously stated, sent First Assistant Sorensen back to the engineroom with the or

der to abandon ship. As the shells were still exploding on the starboard side, the chief mate told Bos'n Dewise W.

Caldwell to release the forward port side life raft. Second Mate O'Connell jumped first. As the men followed, one of

them fell on O'Connell's leg and broke it.

About this time another shell exploded and Second Cook Boleslau Zawistowsky was killed.

The-starboard raft forward was launched by Able Seaman Bjarne Johnsen, who swam to it and later picked up Third

Assistant Engineer Arthur D. Whittaker. The life raft on the after deck, port side, was released by Able Seamen John

P. Lang and Sven E. Roos, assisted by several Navy gunners; they all managed to get aboard and later rowed toward

O'Connell's raft; when they reached it, they took some of the men off to even up the loads.

By this time, Chief Mate Fudske had started to lower the only lifeboat that could be launched-No. 1, on the starboard

side forward. Sorensen found the chief mate trying to do the job alone and went to help him, followed by Electrician

Stoller. The enemy fire continued and Fudske was wounded as the boat was being lowered, but he disregarded his

painful injury and held the boat alongside until McTaggart and Bowen arrived. It was soon evident that the lifeboat had

been riddled with shrapnel holes, for it sank to the gunwales and nearly filled with water, supported only by the buoyan

cy of the air tanks. Before the falls could be released, a shell exploded against the ship's side directly over the boat.

This shell mortally wounded the chief mate. Chief Engineer McTaggart then took command.

Chief Officer Fatally Injured

As McTaggart tells the story of the lifeboat, "Fudske was badly wounded. It was first necessary to get his arm out of

the lifesaving suit he was wearing. When Bowen started to apply a tourniquet, Fudske refused to stay quiet. Despite

the pain, he helped release the falls. He was a great guy, a quiet young chap; I never heard him raise his voice when

he talked to the crew. His last words were: 'Never mind me, fellows. Try to get the boat away!'"

When the attack began, Ordinary Seaman Vaught, then on lookout on the foc'sle head, ran aft to get his lifesaving suit.

On the port side, aft, he was hit by a shell which shattered his leg. Third Assistant Whit-taker, Pumpman Eberling, and

Messman Ragnar F. Pedersen carried Vaught to the second assistant's room, placed him on the bunk, and twisted a

tourniquet around his thigh. The injured seaman died before anything further could be done for him.

On the after boat deck. Oiler Irving C. Wilson received a shrapnel wound in the head which soon caused his death. The

next day, his body was found near that of Utilityman Henry H. Scardora, who must have died after Wilson, as his shirt

was found tied like a bandage around Wilson's head. They were both hit by the same shell. In death, young Henry

Scardora had a smile on his face; he was twenty-two years of age.

Sprayed by Machine Gun Bullets

To return to McTaggart's account :

"At first there were six of us in the lifeboat—Chief Mate Fudske, the three engineers. Electrician Stoller, and Messman

John Daley. Daley had been lifted out of the water while they were waiting for Bowen and me. Half his hand was torn

off by a shell; they had patched him up as best they could, but he soon died. Stoller was badly wounded by the shell

that killed Fudske. Another piece of shell went through Soren-sen's right wrist, broke it, and left a fragment sticking

there. I got some shrapnel through my fingers, neck, and' shoulders, but didn't even realize it until later.

"As the shellfire had cut the falls, we were finally able to get the boat clear. It was nearly full of water and the dead and

injured were lying around so that we couldn't row. Bowen, Sorensen, and I decided to jump overboard and push the life-

boat away from the ship. We thus lightened the boat and also used it as a shield, holding it between us and the gunfire.

It took courage for Sorensen to go over the side with us; he was in agony from his wounded wrist. But we all paddled

along, edging the boat tar enough from the ship to be out of the line of fire. A machine gun sprayed the sea near us se-

veral times, but we were not hit.

"We floated around nearly two hours and managed 'to pull the boat about 700 feet away from the burning vessel. It was

lucky for us that we had reached such a distance because the submarine, shortly before daybreak, fired a torpedo into

the starboard side of the Esso Bolivar, blowing part of the cargo several hundred feet into the air. Three of four compart-

ments were flooded. The ship took a bad starboard list, but stayed afloat."

Submarine Leaves

For nearly two hours the enemy submarine had tried to destroy the tanker by shellfire without using a valuable torpedo.

It was fortunate for the ship and her crew that the Esso Bolivar was not carrying a cargo of oil.

"The submarine circled the ship twice," McTag-gart continued, "playing a searchlight over it. Suddenly two star shells

exploded overhead. When the brilliant flares lighted up the whole vicinity, the submarine submerged and we never saw

it again. We found out later that the star shells were fired by a naval vessel.

"Feeling it was now safe to get back into the boat, we tried to patch up the wounded, but all the first aid equipment was

wet. Stoller was holding his clothing against his wounds to stop the bleeding. We placed the bodies of Fudske and Daley

in the stern and made the injured men more comfortable by placing life jackets under their heads.

"There was not room to use more than two oars. Bowen and I rowed while Sorensen handled the tiller. We got under

way, but the boat was so low in the water we could only creep along.

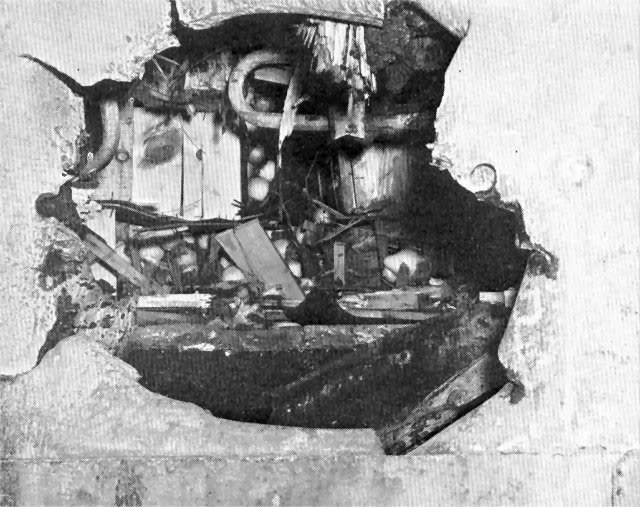

A jagged hole opens into the ship's refrigerated space, amidship, starboard side.

Pull Men From Sea

"In the darkness we heard men calling out that sharks were attacking them. At their cries for help we headed in their

general direction, shouting encouragement. I recognized 'Tex' Richardson's voice pleading with me to hurry up. As we

rowed closer I saw three men bobbing up and down in the waves. Besides Richardson, there were Fireman-Watertend-

er Lauman and Seaman Peter B. McCloskey. We pulled them into the boat and found that 'Tex', powerful as he was,

had been much weakened by exhaustion and loss of blood. A shark had ripped his hand open, well past the wrist."

As previously mentioned, Richardson had heaved the two wounded Navy gunners-Robert H. Lewis and Lawrence R.

Creps-over the side of the ship and had dived in after them.

Chief Cook Nemuel J. Camp, in an interview for this history, told what happened.

"When Richardson threw the wounded Navy men overboard," he said, "I followed them, with Lauman and McCloskey.

Lauman swam over to support Creps while McCloskey and I joined Richardson in assisting Lewis. Lauman called for

help in keeping Creps afloat and Richardson and McCloskey responded, leaving me in charge of Lewis, as I was wear-

ing a rubber life-saving suit. I held Lewis on my back.

"It was not long before Richardson yelled 'Sharks!' and drew his knife. He struck out with the blade to defend himself

and his companions. He could not save Creps, but the sharks were finally driven away."

By this time it was near sunrise and the men in the lifeboat saw Camp and Lewis and rescued them. Later they picked

up Machinist Low. When McTag-gart and his companions added the three men to the boat it started to submerge. Life

jackets were therefore taken off and placed under the thwarts to give the boat buoyancy. But when more survivors were

found-Third Mate Owen and Radio Operator Alvis Jones, both wearing lifesaving suits-they were towed because the life-

boat would not stand their extra weight. To save Camp and Low, it was necessary to lighten the load in the nearly sinking

boat and there was only one way to do this. The bodies of Hawkins Fudske and John Daley were lowered into the sea.

When O'Connell's raft joined that of Whittaker and Johnsen four men boarded the latter to man the oars and search for

survivors; they were Caldwell, Eberling, Sampson, and Myers. Rowing toward what they thought was wreckage with

men clinging to it, they found it was the lifeboat.

One Man Still Aboard

Meanwhile, the third raft, manned by Lang, Roos, and several Navy gunners, had remained nearest to the ship. After the

submarine disappeared and the star shells had burned out, they saw a flashlight moving along the rail of the Esso Bolivar.

Astonished to find a living man on board, they rowed nearer and heard shouts of "Don't leave me!" Going alongside, they

rescued Wiper Matthew Carlo, who had received a head wound and was unconscious at the time the ship was abandoned.

"After daybreak," McTaggart reported, "we sighted what proved to be Whittaker's raft with six men on it; about half a mile

away, they were rowing in our direction. So slow was their progress that it took nearly two hours to reach us. When they

came alongside we managed to transfer all but Gallavan and myself to the raft, thus lightening the boat so that it came up

in the water and at last we could see the holes. Some of them were three inches in diameter;

We had no tools except a knife. With the help of Caldwell and Eberling we took the air tanks out one by one and plugged

the shrapnel holes in back of the tanks, also stopping holes in the tanks themselves after letting the water out. It was lucky

for us that the tanks were filled with kapok.

Plugged Holes With Boots and Vegetables

"Some of the men on the raft were wearing complete lifesaving suits w^ith heavy rubber boots; we cut the boots away

and pulled them through the large holes as stuffing. The smaller holes should have been filled with wooden plugs, but it

would have taken too long to whittle them. There were vegetables floating around—part of the commissary stores hurled

out of the ship through the huge hole made by the torpedo. We picked up scores of parsnips and carrots;

they were ideal for plugging the smaller holes.

"After some discussion, we decided against going back to the ship. The wounded were in bad condition and the Esso

Bolivar was still on fire. We had drifted a considerable distance and the current was against us.

Picked Up by Minesweeper

"Finally some one sighted a small vessel headed our way. Soon afterward, a civilian plane appeared, carrying news

photographers who came out to take pictures of the ship. Then a military plane dropped a smoke bomb alongside the

lifeboat and Whittaker's raft so that the approaching vessel would not miss us. She proved to be the minesweeper USS

Endurance, which reached us before noon and picked us up, having previously rescued the men on the other two rafts.

"When the Endurance arrived, some of us were anxious to go back aboard the ship, but the commanding officer of the

minesweeper would not agree to this; the wounded men needed attention and the sooner they could be hospitalized the

better.

"On the way to Guantanamo the destroyer USS Stringham met us. Coming alongside the Endurance, she took Third Mate

Owen and Seaman Johnsen on board, put a medical officer on the minesweeper to take care of our injured men, and then

speeded ahead so that Owen, the only uninjured deck officer of the Esso Bolivar, could report the condition of the ship to

the commandant of the Naval Base. After refueling at the base, the Stringham returned and stood by the damaged and

drifting tanker. When the Endurance docked at Guantanamo, a Navy. ambulance was waiting for us at the pier."

The men hospitalized at Guantanamo or treated at the hospital were Second Mate Eldridge J. O'Connell. Chief Engineer

Thomas J. McTaggart, First Assistant Engineer Carl L. Sorensen, Radio Operator Alvis Jones, Electrician Abraham Stoller,

Steward William Fisher, Chief Cook Nemuel J. Camp, Able Seamen Charles D. Richardson, Peter B. McCloskey, Carl J.

Sampson, and Bjarne Johnsen, Ordinary Seaman Frank Zabroski, Machinist Charles H. Low, Oilers James J. Gallavan

and Roy L. Alien, Storekeeper Louis A. Dinnebeil, Fireman-Watertender Joseph J. Sokolowski, and Wiper Matthew Carlo.

"On the trip in," McTaggart said, "we had sent a radio message to the commandant of the Naval Base, saying we were

sure that if we could return to the ship we could bring her to port. The commandant, Captain (later Rear Admiral) George

L. Weyler, U. S. Navy, came through handsomely; he sent a Navy plane out to the Esso Bolivar .to take photographs. Also,

at 10:30 o'clock that evening, he and other naval officers visited me at the hospital; they showed me the pictures and ask-

ed questions about the ship. They wanted to know what equipment would be needed to salvage the vessel.

"The naval officers agreed we had a chance to save the tanker and the commandant said he would assign the net tender

USS Mulberry to take out the men able to go. He would also provide a salvage party of 25 men."

Back to the Ship

In addition to Chief Engineer McTaggart, the men who returned to the ship were Third Mate Owen, Second Assistant

Engineer Bowen, Third Assistant Engineer Whittaker, Radio Operator Jones, Pumpman Eberling, Able Seamen Johnsen,

Lang, Myers, Phillips and Roos, and Firemen-Watertenders Florio, Lauman, and Sokolowski.

As the Mulberry was scheduled to leave at midnight, McTaggart asked the senior medical officer, Captain C. J. Brown,

MC) U. S. Navy, to give him a discharge from the hospital, insisting that his shrapnel wounds were healing. The Navy -

released him, deciding that a man of such spirit would get along all right.

The Mulberry reached the Esso Bolivar about 9 o'clock in the morning, March 9. In addition to the USS Stringham, a Navy

tug was standing by. The tanker, still burning, had a 20 degree list to starboard.

Pumpman Eberling, a capable and experienced man who knew the ship well, took a good look at her before he went

aboard. He told the chief engineer he could shift ballast and straighten her up; and he proceeded to do so in a commend-

ably short time.

McTaggart, with Second Assistant Bowen, Third Assistant Whittaker, and Firemen-Watertenders Lau man, Sokolowski,

and Florio, went below and made an inspection tour, noting just what damage had been done to the machinery. The probl-

em that claimed their first attention was the fire still burning in the paint locker. They had a good supply of carbon tetrach-

loride and foam which, they poured down the

ventilators leading to the locker. As the chemicals were not sufficient the next thing was to raise steam arid use the smo-

thering system; but to raise steam in this emergency was no simple matter.

The auxiliaries necessary to operate the main engine of the Esso Bolivar are driven by steam or by electricity from steam

driven generators. Moreover, electric pumps supply fuel for the steam boilers. How could electric current be obtained to

get up steam in the boilers, provide electric light, make repairs, and then operate the main engine? The unusual foresight

of the chief engineer had previously provided the exact answer.

A few days before the attack, McTaggart had been thinking about the small Diesel generator installed for the degaussing

system and the possibility of using it in just such an emergency to supply electricity for the auxiliaries. He had asked

Electrician Stoller to make a copper jumper to take current from the degaussing generator to the main bus bars. This jump-

er was kept in the chief engineer's office so that he would always know where to find it.

Due to damage from shellfire and the starboard list of the ship, McTaggart's office had four or five feet of water in it; every-

thing was scattered about and either floating or under water. After diving a dozen times into the mess and groping around,

he finally found the jumper. It was literally the key to the success of the entire salvage operation.

Electric Current Restored

When the jumper had been put in place across the contacts on the switchboard, the degaussing system's Diesel generat-

or was started by means of its batteries and immediately there was electric current throughout the Esso Bolivar.

By this time Pumpman Eberling, by expert handling of the right valves in succession, had managed to gravitate the ballast

to tanks on the port side until the ship was practically on an even keel. He had done this job in half an hour.

The next step was to raise steam to smother the fire in the paint locker and operate the fire pumps so that the hoses could

be used to fight the fire in the refrigerating room. As soon as possible, the damage to the steam lines was repaired and the

paint locker fire was soon extinguished. Then the emergency controls for the steering engine were connected.

With a good head of steam in the boilers, the chief engineer and his men finally got the cooling water and lubricating oil

pumps for the main engine started. By that time, Navy men, finding the engineroom telegraph useless, had rigged an emer-

gency telephone line from the bridge to the engineroom. About 2 p.m., after thoroughly examining the main engine. Chief

Engineer McTaggart notified the naval officer on the bridge that he was ready to get the ship under way. A few minutes later

an order was given to proceed slowly and the speed was gradually increased to about 8 knots.

"McTaggart's Miracle"

What happened when this brilliant achievement started the ship in motion was described by former Able Seaman Harold

L. Myers, who was working on deck at the time: "We called it 'McTaggart's miracle,' " he said. "The naval officers were get-

ting ready to tow the ship and the tug was just getting a strain on the hawser when the chief engineer reported to the bridge

he was ready to start the main engine. When the men on the tug were told to cast off and the Esso Bolivar started to move

under her own power, I never saw so many surprised people. The tug barely cast off in time and was almost towed by the

ship. Her men had to cut the hawser."

The Esso Bolivar, with her escort vessels, arrived at Guantanamo about 5 o'clock that evening but could not dock because

of the fire still burning in the massive cork insulation of the refrigerating room. The ship anchored in the bay for three days,

during which her crew and the Navy salvage party, working in relays, made every effort to put the fire out. Finally they had

to take a torch, burn holes in the bulkheads, and tear out the cork. As soon as the fire was extinguished, the ship was dock-

ed for temporary repairs.

On March 11, 1942, Captain James M. Stewart, Able Seaman Basil E. Vaught, Oiler Irving C. Wilson, and Utilityman Henry

H. Scardora were buried in the cemetery of the United States Naval Base at Guantanamo, Cuba. During the religious service

held by Navy chaplains for these men of the American Merchant Marine "killed in action", all their shipmates who could leave

the hospital and the ship stood with heads bared on the sandy hillside among the palms.

On March 10, a party of workmen from the Naval Base, in charge of Chief Machinist Frank Hendricks, boarded the vessel.

As Hendricks reported, they had received instructions to place themselves at McTaggart's disposal for whatever work he re-

quired.

"My first assignment," the chief engineer said, "was to take a blank out of the cargo line in the forward part of the vessel

so that we could use the drinking water pumps for pumping out the flooded tanks. We were then able to pump the fore part

of the vessel dry. The next job was to cut a hole between No. 9 starboard wing tank and the cofferdam; this enabled us to

gravitate the water from the after part of the ship into the cofferdam, from which it was pumped overboard by the pumps in

the engineroom.

Dive Under Water To Set Valves

"The hole made by the torpedo was about 50 feet long and 35 feet deep, extending downward almost to the keel. The main

pumproom, adjacent to the hole, was flooded, and it was necessary to dive into 20 feet of water to set the pumproom valves

and remove the cover from the strainer box so that the pumproom could be pumped dry. As the only diver was ill, we made

a diving helmet out of the fresh air breathing apparatus and Pumpman Eberling went down and did the necessary work.

"We then started one of the main cargo pumps and were able to get the water down to about 10 feet, but could not get it any

lower because there was a large hole in the pumproom bulkhead near the bottom. When Eberling, who had kept up his stre-

nuous work for hours, showed signs of fatigue, I decided to replace him and went down into the water, placing a mattress

over the hole. It was pushed out of the hole by water pressure, but when we first covered the hole with boards, the mattress

stayed in place. We were then able to run the pumps slowly and keep the pumproom dry.

"The following day the Navy workmen at the base made a steel plate and welded it over the hole inside the pumproom. After

caulking the seams in the after bulkhead with rags, which was done by diving under the water on the opposite side, we were

able to make the pumproom watertight and the bulkheads were^ then shored up with heavy timbers to prevent them from col-

lapsing.

"After that we ballasted the ship to give her a port list and the Navy workmen secured some steel beams and braced the hull

in way of the torpedo hole, starboard amidships. About 30 large shell holes in the hull and superstructures were patched-there

were about 120 holes in all. The steering gear controls and the pipelines on deck and in the engineroom auxiliaries were also

repaired by the Navy."

On March 12, Mr. Guy L. Bennett, Port Engineer, arrived to represent the Company in transactions with the Navy authorities

and in matters concerning emergency repairs and personnel. He was accompanied by replacement officers-Captain Abbo

H. Kooistra and Chief Mate Edwin Wright. They were followed by Second Mate John Koyl, who arrived March 17.

In addition to Mr. Bennetfs report on the condition of the Esso Bolivar he wrote to the Company management as follows: "I

should like to call to your attention the admirable cooperation of the Navy personnel while this ship was being made ready

for the voyage to a U. S. port to carry out permanent repairs. Everyone connected with the emergency repairs did his utmost

to get the ship out with the minimum of delay—from the commandant at Guantanamo, Captain G. L. Weyler, and the captain

of the yard, Commander C. La F. Surran, to the various section ' heads . . . The injured received every attention in the Naval

Hospital . . . Captain Weyler provided the Esso Bolivar with protection all the way from Guantanamo to Pensacola ... I cannot

speak too highly of the assistance given, in ways too numerous to mention, by the entire personnel of the Navy staff at Guanta-

namo and the naval attaches at Havana."

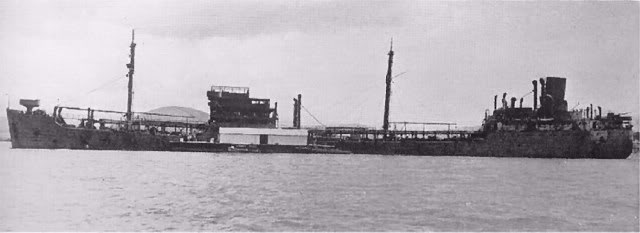

"Esso Bolivar" in Cuba after temporary repair in 1942 after a torpedo hit.

Navy Tribute

The Navy, in turn, paid a tribute to the chief engineer of the recovered tanker. On April 15, 1942, Rear Admiral R. M. Griffin, U. S.

Navy, Director of the Naval Transportation Service, wrote to the Company's management as follows:

"I take pleasure in quoting the following comments from a recent report on the tanker Esso Bolivar, made by the Commander,

Transport Division Eleven: "The party from Naval Operating Base Guantanamo included some members of the regular crew of

the tanker. Among them was the chief engineer, Mr. Thomas J. McTaggart. This man made a particularly good impression. He is

intelligent, courageous, and industrious. His work in connection with the salvage was invaluable. It is recommended that the

Navy Department bring this to the attention of the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey."

Finally the vessel was made absolutely dry with the exception of the tank where the torpedo hit. Emergency repairs completed,

the Naval Base furnished lifeboats from other ships and the tanker that would not sink was ready for sea.

On March 25 the Esso Bolivar with her naval escort left the Guantanamo Naval Base bound for Mobile, Alabama, and after a vo-

yage without incident arrived at Mobile on March 30. Permanent repairs were begun April 16 and completed July 24. The ship

was as good as new. On August 6, 1942, with a full cargo, she left Corpus Christi, Texas, for New York and thereafter resumed

her regular voyages to Aruba.

Captain James M. Stewart entered the Company's service as a third mate on August 10, 1918, and had been a master since

April 29, 1926. He was assigned to the command of the Esso Bolivar on January 15, 1942, less than two months before he lost

his life in the sea service of his country.

Chief Engineer Thomas J. McTaggan joined the Company September 21, 1931. He has been a licensed officer since January

19, 1934, and a chief engineer since August 16, 1939. After the attack on the Esso Bolivar he continued to serve as chief engi-

neer of the vessel until August 18, 1944, when he was transferred to the Port of New York Office, becoming an Assistant Port

Engineer. Since October, 1945, Mr. McTaggart has been Port Engineer.

The first Liberty ship honoring a member of the Esso fleet personnel lost by enemy action was the SS Hawkins Fudske, nam-

ed for the chief mate of the Esso Bolivar. Launched at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard, Baltimore, Md., on September 11, 1943,

it was christened by his widow, Mrs. Hawkins Fudske.

Ten members of the crew of the Esso Bolivar were on other tankers sunk or damaged by enemy action before or after March 8,

1942.

Two were lost: Able Seaman John P. Lang (C. 0. Stillman, June 5, 1942) and Oiler Roy L. Alien (C. J Barkdull, in December, 1942).

Eight were survivors of enemy action: Machinist Charles H. Low {Charles Pratt, December 21, 1940);

Chief Cook Nemuel J. Camp (steward,' }. A Mowinckel, July 16, 1942); Able Seaman Peter B^ McCloskey (H. H. Rogers, February

21, 1943) ; Able Seaman Harold L. Myers (ship's clerk. E. G. Senbert February 23, 1944); Able Seaman Charles D. Richardson

(H. H. Rogers, February 21, 1943); Able Seaman Syen E. Roos (J. A. Mowinckel, July 16, 1942); Ordinary Seaman Stanislaus

Skadovura, a brother of Henry H. Scardora, who spelled his name differently - (C. 0. Stillman, June 5, 1942); and Fireman-Water

tender Joseph J. Sokolowski (7. A. Mowinckel, July 16, 1942, and H. H. Rogers, February 21, 1943).